The Competive Nature of Capitalism & Our (Very) Sick Society

Some thinkers of the past wrote about its alienating, crippling and inhumane qualities. They were quite prescient of capitalism's quiddities.

There is a saying, a strongly held belief, if you will, that says capitalism is the best economic system, bar none. That it is capitalism that raises people out of poverty; that it is capitalism that leads to all our innovation; that it is capitalism that brings about freedom; and that any other political-economic system can never match the benefits and the common good that capitalism has brought to us, and the proponents of capitalism, would add, continue to do. The advocates of capitalism often quote how many people have been pulled out of poverty, because of capitalism. Such proponents usually use India and China as their prime example of why capitalism is so good, wonderful and need not undergo any (major) changes. Well, as is always the case, there is much more to the story and the numbers cited.

For example, if the global baseline for poverty is a little more than two dollars a day, what is that really saying? That a large part of the world subsists on two dollars a day? Is that enviable? I will explain in a future post on why these figures and examples are misleading, leading people to the wrong conclusions. That the problems with poverty on a global scale are far greater than capitalists would like to admit. Or, perhaps, the super-rich no longer care or feign to care.

Now, I used to believe and say that my quibble is not with capitalism, per se, but with how capitalism has evolved—and it has evolved—into the system currently in place in America, Canada, Britain, France as well as in Russia and in China, the latter of which is officially politically communist, having the Communist Party of China as its sole political party. Whether it is sufficiently communist or not, I will leave to the political scientists to argue and debate. Needless to say, it has communist principles in place, which we have seen are clashing with those of capitalism, which today is more than an economic system. Capitalism today represents a complete and comprehensive worldview that essentially says, “let the markets decide” and “enlightened self-interest” is an excellent idea on which to base a system of political economy.

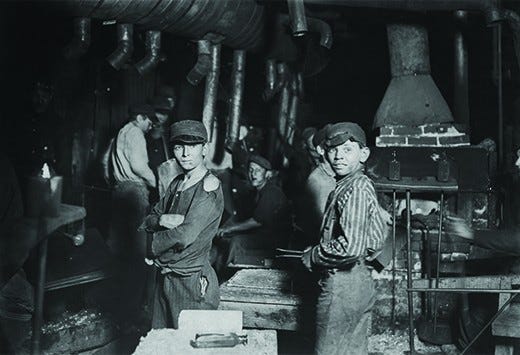

My quibble now, is based on a question, of why it has become so cruel, having as its basis a competitive winner-take-all approach. If capitalism is concerned with fewer restrictions for business, then we have seen the results. Capitalism can be boiled down to the idea that money is the prime motivator of people, that hard work leads to opportunity and those who have a lot of money will give work to those that don’t. In other words, that capitalism provides jobs. There are many questions. Has it met that expectation? Is there something wrong with the idea of a benevolent employer? Does it almost sound like a benevolent dictator? How many (or few) rights do workers have? Why do workers have so little freedom in the workplace? Why are organizations structured in an hierarchical way? Who benefits from such a structure?

All of these questions are not new. They were raised and answered by quite a few thinkers, including two famous individuals, Karl Marx [1818-1883] and Albert Einstein [1979-1955], both born in Germany to Jewish families, both not placing much stock in their Jewish origins and both holding humanistic ideas.

This is an excerpt of what Marx had to say in “Comments on James Mill” (1844), part of Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, which were first published in 1932, almost 50 years after his death. I cite from the Wikipedia entry:

Let us suppose that we had carried out production as human beings. Each of us would have, in two ways, affirmed himself, and the other person. (i) In my production I would have objectified my individuality, its specific character, and, therefore, enjoyed not only an individual manifestation of my life during the activity, but also, when looking at the object, I would have the individual pleasure of knowing my personality to be objective, visible to the senses, and, hence, a power beyond all doubt. (ii) In your enjoyment, or use, of my product I would have the direct enjoyment both of being conscious of having satisfied a human need by my work, that is, of having objectified man's essential nature, and of having thus created an object corresponding to the need of another man's essential nature ... Our products would be so many mirrors in which we saw reflected our essential nature.[8]

Now, I am not a Marxist, but this does not suggest to me that I ought to ignore everything Marx wrote or said. He was right about worker alienation. He was right about how far workers, wage earners and professionals, are from meeting the human needs through work. People today are so far removed from what they are producing, that money becomes the chief and often the only motivating factor in his or her continuing the effort. This alone explains much what ails our society.

Then there is the brilliant work of Pyotr (Peter) Alexeyevich Kropotkin [1842-1921], a Russian naturalist and anarchist philosopher, who published Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, in 1902. Kropotkin published it as a counterweight to the prevailing arguments of Herbert Spencer, Consider this salient point in the “Introduction”:

After having discussed the importance of mutual aid in various classes of animals, I was evidently bound to discuss the importance of the same factor in the evolution of Man. This was the more necessary as there are a number of evolutionists who may not refuse to admit the importance of mutual aid among animals, but who, like Herbert Spencer, will refuse to admit it for Man. For primitive Man – they maintain – war of each against all was the law of life. In how far this assertion, which has been too willingly repeated, without sufficient criticism, since the times of Hobbes, is supported by what we know about the early phases of human development, is discussed in the chapters given to the Savages and the Barbarians.

Again, I am not an Anarchist, either. I do, however, like the free flow of ideas and am ready to entertain them at my age. First, we ought to get a working definition of anarchy as a political system. What it is not chaos and lawlessness. What it is a decentralized system of governance, which has its roots in classical liberalism. Political anarchy is the opposite of the top-down, rules-heavy hierarchical system of capitalism. I suspect capitalism can only work under such a structure. Here is one explanation of political anarchy that I found useful. In “A Brief Explanation of Anarchism” in Philosophy Now (2018), Nick Gutierrez writes on why anarchists reject the idea of the state as a source of authority:

So the core principle of anarchism is rejection of the state. But what is the state? It’s typically at this point in discussions of anarchism that fine details fall by the wayside, as many seem to take the dictum that ‘anarchism opposes the state’ as a broad decree for its followers to resist any and all forms of social organization – a prospect which many find disturbing. This notion of anarchism, however, is inaccurate. I will again turn to Bookchin for what I take to be the best explanation. By rejecting the state, he says, “I don’t mean the absence of any institutions, the absence of any form of social organization. ‘The state’ really refers to the professional apparatus of people who are set aside to manage society, to preempt the control of society from the people” (Anarchism in America). So for Bookchin, the state typically includes such entities as the military, judges, and politicians. In other words, the state consists of those categories of people who are given a special privilege or degree of control over the rest of society, but don’t typically act from within it. This status is sometimes referred to as ‘sovereignty’. Yet Bookchin emphasizes that anarchism does not oppose social organizations in principle. Rather, social organizations only become problematic when they take the form of a state. Not all organizations are states, and accordingly, anarchists take issue with some organizations but not others. Labor unions, for example, are a kind of organization that some anarchists would deem to be beneficial for society.

That is Murray Bookchin [1921=2006], the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants, the American social theorist and political philosopher, who grew up in New York City. Another key part of the essay is why states are problematic:

While there is hardly any complete consensus among anarchists about which characteristics of a state are problematic (there is hardly any complete consensus among anarchists about many things), Miller points to several themes that recur in anarchist literature. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) claims that “to be governed is to be at every operation registered, taxed, forbidden, licensed, extorted, robbed, condemned, shot [and] betrayed” (quoted by Miller in Anarchism, p.6), among other things. Referencing Proudhon, Miller agrees that states are both ‘coercive’ and ‘punitive’, reducing people’s freedom “far beyond the point required by social co-existence” and “enacting restrictive laws and other measures which are necessary, not for the well-being of society, but for [the state’s] own preservation” (Anarchism, p.6). Additionally, states inflict “cruel and excessive penalties on those who infringe its laws, whether or not those laws are justified in the first place.”

That is David Leslie Miller [born in 1946], an English political theorist and professor of political theory at University of Oxford. The book cited, Anarchism, was published in 1984.

Now, back to Kropotkin and his general argument, which, simply put, is that humans, like non-human animals, are more cooperative than combative. That cooperation is a great part of the evolutionary process, and that Spencer misunderstood what Darwin was putting forth and placed a Hobbesian understanding to it, i,e, the state of nature is a state of war, in constant battle and fraught with divisive struggle. Kropotkin’s arguments, from what I have read thus far sound intriguing and more amenable to a society in which I would like my children to enjoy. I want to read a little more, since his name is synonymous with anarchism in the liberal tradition. Mutual aid sounds so much better than constant struggle, working alone, for survival. Mutual aid is about working together, where each member benefits, and not only the ownership class, which is the case now.

Let’s now consider Albert Einstein, who in addition to being a great scientist, a great theoretical physicist, he was also a great humanitarian and a socialist. I am a classical liberal with socialist leanings, so Einstein’s ideas and views are highly appealing to me. He wrote the following in Monthly Review, originally published in May 1949 and republished on May 1, 2009; Einstein writes:

Production is carried on for profit, not for use. There is no provision that all those able and willing to work will always be in a position to find employment; an “army of unemployed” almost always exists. The worker is constantly in fear of losing his job. Since unemployed and poorly paid workers do not provide a profitable market, the production of consumers’ goods is restricted, and great hardship is the consequence. Technological progress frequently results in more unemployment rather than in an easing of the burden of work for all. The profit motive, in conjunction with competition among capitalists, is responsible for an instability in the accumulation and utilization of capital which leads to increasingly severe depressions. Unlimited competition leads to a huge waste of labor, and to that crippling of the social consciousness of individuals which I mentioned before.

This crippling of individuals I consider the worst evil of capitalism. Our whole educational system suffers from this evil. An exaggerated competitive attitude is inculcated into the student, who is trained to worship acquisitive success as a preparation for his future career.

“That crippling of the social consciousness” is so well put. As is the cause of it: unlimited competition, an “exaggerated competitive attitude.” This rings true today. It has the stamp of authenticity, the stamp of reality, the stamp of truth. Such is the hallmark of capitalism; without the competition to acquire things, without that acquisitiveness nature, there is no capitalism, there is no severe inequality, there is no huge wealth gaps and there is no reason for poverty.

I used to think that the cruelties and competitiveness of capitalism could be mediated, reformed, made less harmful. By government legislation. It could have been, even if only moderately and modestly, at one time. That ship has sailed long ago. Corporations will find ways to circumvent any new possible regulations, which will be weak and ineffective, watered down. Now, in my older years, I no longer view this as possible. This cruelty is not a bug of capitalism; it is a feature designed into its system.

Capitalism is working precisely and methodically the way it was designed, its gears of commerce enabling the rich to remain rich: they feel it is their entitled right to the selfish individualistic pursuit of money, wealth and property, without any ethical or moral impediments. This means money flows to the top, as it has always has, which is its systemic intention. Yes, it is cruel; yes it is callous; and yes it is uncaring. Greed and the feeding and rewarding of the worst impulses of human nature drive the system. But humans are not content and happy with such a system, so they find ways to escape, with drug and alcohol abuse, along with overeating leading to obesity all being sure signs of an unhealthy society—not only physically but also in non-material or spiritual ways.

Some of the ideas contained in the above-mentioned political philosophies do have merit. But none are likely to be implemented. Capitalism is entrenched in our society, with all of its awkward and inhumane quiddities. There is also the very real connection between capitalism and increased violence and militarism, which has reams of evidence to support such an unpopular idea. Yet, few doubt that capitalism is brutal, notably in America with its long history of slavery. The inequalities, the cruelty, the brutality are accepted as normal, few seeing it as sick and abnormal. That being the case I do not foresee our society replacing it with a more sane political economic system any time soon. Thus, I sense that our society will become even less healthy than it is now, and likely more aggressive, more violent, more sick. Inequalities will increase, in keeping with what capitalism does best. In the end, the Siren Song of Capitalism is alluring, calling people to the shores of opportunity for riches, acquisition and greater consumption. A few succeed, but only in accordance with Capitalism’s narrow rulebook; most, however, crash on the rocks of despair, ummet desire and desperation, never seeing the error of their ways.

So, we have come to the end of my argument. In this essay, I have attempted to point out some of the many of capitalism’s weaknesses and its terribly destructive nature. There is one more that requires elucidation, if only briefly. It is one that offends my sensibilities of good the most. Our political economic system terribly cripples our ability to see beauty, truth and justice, much of it contained in the natural world, if only we seek it. Capitalism’s blunt and crude, yet highly functional instruments, make a mockery of such noble values that can and do elevate our being, elevate our society. Capitalism seems good on a surface level, but it rides on malevolent forces; its energy negative and not life-affirming, its forces dark. I have been reading much lately on how to re-navigate my world, to places of truth and most of all, to beauty, and in particular to the beauty of Nature and the natural world. In my mind, beauty always contains truth, which is a hallmark of justice. Without these, our society is a much poorer and more brutal place.

Merci et à bientôt.

Next week, I will continue this discussion by looking at the effects of capitalism on our modern society.

I not only share your concerns about the nature of capitalism, I also think it's so important for us to engage with political philosophy and not merely political science. Political science is, by and large, the practice of politics within a particular given system. Political philosophy, by contrast, invites us to contemplate the underlying structure and characteristics of a political-social system. In my studies I have found many valuable insights from schools of thought including those I did not fully identify with. Anarchism and the various thinkers critical of capitalism are sadly marginalized, to put it very mildly, and our political discourse.

A few works and resources that come to mine and reading your piece. The anthropologist, James Suzman does an amazing job of debunking the myth that grueling labor and a dog eat dog mentality are essential to our species: https://youtu.be/P4SDBVaUboc?si=bvUvfXrcdYq6Y3Nu

Richard Wolff's YouTube channel, democracy at work offers and invaluable counterweight to the dominant political philosophical narratives: https://youtu.be/7eRBl7quf1g?si=emf91HgDMAGgTw1a

On Karl Marx, I have learned so much from Eric Fromm's book, "Marx's concept of man." It's a book I find myself coming to again and again for new fresh insights about the humanism that has too often been left out of analysis regarding Marx. Fromm argues convincingly, in ways that I think are still applicable today, that many of Marx's adherents lost track of the elemental humanism underlying his philosophy.

I am aware of Richard Wolff and his erudite analysis. I will look up James Suzman. Thanks for the recommendation.

I am also looking at expressions more closely, particularly ones that intimate that it is non-human animals that are more cruel than the human kind. The expression "dog-eat-dog" is emblematic of the human idea of superiority and misplaced analysis. Do most dogs eat other dogs, even figuratively? No, not that I know or aware of.

How about humans under a competitive capitalist system? Quite often. Perhaps a more accurate assessment of our political economy is human-eat-human. Figuratively, of course.